Στο αμερικάνικο περιοδικό The Tablet, υπάρχει εκτενές άρθρο για την αποκάλυψη του μνημείου για τους 139 τρικαλινούς Εβραίους που πέθαναν στα τρατόπεδα συγκέντρωσης των Ναζί. Το υπογράφει η κ. Margarita Gokun Silver, με δηλώσεις του Δημάρχου Τρικκαίων κ. Δημήτρη Παπαστεργίου και σε αυτό αναγράφονται όλα τα σχετικά με το σημαντικό τριήμερο μνήμης που διοργανώθηκε τον περασμένο Νοέμβριο στα Τρίκαλα.

Ακολουθεί το άρθρο:

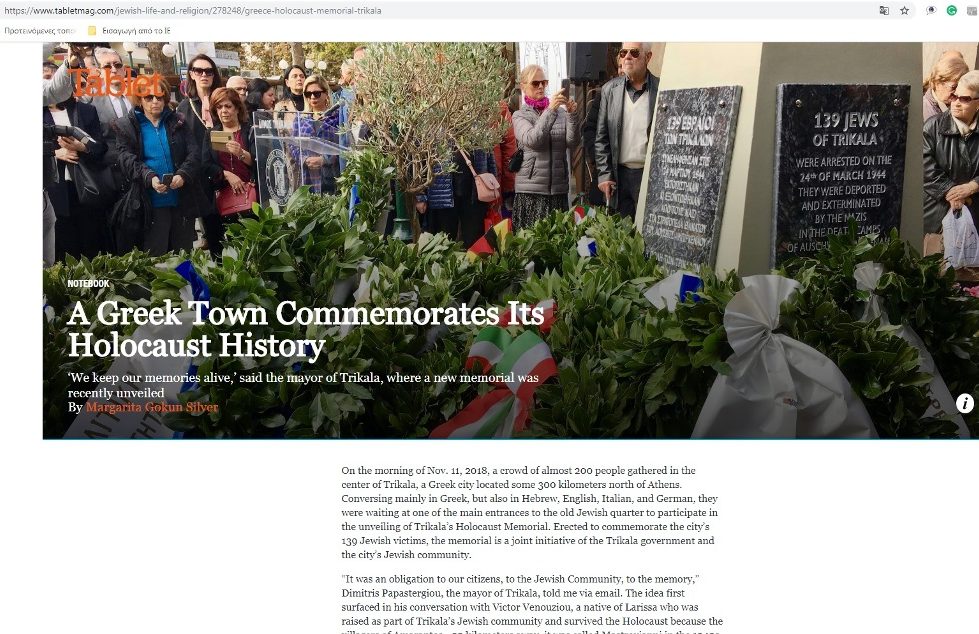

On the morning of Nov. 11, 2018, a crowd of almost 200 people gathered in the center of Trikala, a Greek city located some 300 kilometers north of Athens. Conversing mainly in Greek, but also in Hebrew, English, Italian, and German, they were waiting at one of the main entrances to the old Jewish quarter to participate in the unveiling of Trikala’s Holocaust Memorial. Erected to commemorate the city’s 139 Jewish victims, the memorial is a joint initiative of the Trikala government and the city’s Jewish community.

“It was an obligation to our citizens, to the Jewish Community, to the memory,” Dimitris Papastergiou, the mayor of Trikala, told me via email. The idea first surfaced in his conversation with Victor Venouziou, a native of Larissa who was raised as part of Trikala’s Jewish community and survived the Holocaust because the villagers of Amarantos—50 kilometers away, it was called Mastroyianni in the 1940s—hid him and his family. Last year Venouziou financed a monument in Amarantos to thank them. “Within five minutes we agreed that the city and the Municipality of Trikala also had to erect their own monument,” Papastergiou said.

The monument designed by the municipality, with input from Trikala’s Jewish community, is in the shape of a tear flanked by railway tracks. In the center is an olive tree and to the side is a column with an inscription in three languages: Greek, Hebrew, and English.

The unveiling brought together members of the Jewish communities of Athens, Thessaloniki, Ioannina, Larissa, Karditsa, Volos, Chalkis, Rhodes, and Corfu, as well as ambassadors and dignitaries from several foreign nations. Organized by the municipality of Trikala with the active participation of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, the Central Board of Jewish Communities in Greece, the Jewish Museum of Greece, and the Italian Embassy in Greece (Italy holds IHRA’s 2018 chairmanship), the ceremony was the culmination of a three-day Holocaust-remembrance program that included exhibitions, concerts, a book presentation, and a documentary screening.

“While Jews are a small percentage of the local population, they are an inseparable part of the history of Trikala, society, and culture,” Jacob Venouziou, president of the Trikala Jewish Community (and Victor’s cousin), said in his speech at one of the events. “The monument reminds us that [Jewish heritage] isn’t something of the past. It is also for the present and the future, an active movement of recognition and defense of cultural and religious diversity, as well as resistance to discrimination.”

*

The history of Trikala goes back to its predecessor, Trike, an ancient city founded around the third millennium BCE. Considered of great importance because of its connection with Asclepius, the god of medicine, the city hosted many healing temples; got a mention in Homer’s Iliad as one of the Trojan War participants; and, in the Mycenaean period, served as the kingdom’s capital. During the Byzantine Empire as well as during the early Middle Ages, Trikala had its share of rulers and invaders until the Ottoman conquest at the end of the 14th century brought a period of relative stability. The city remained inside the Ottoman Empire until the 1881 Treaty of Constantinople made it part of Greece.

Although it’s not clear when Jewish people began to settle in Trikala, some sources mention the presence of Jews in the city during the Byzantine period. They called themselves Romaniotes, spoke Greek with some elements of Hebrew and Aramaic, and worked as craftsmen, traders, and even silk growers. In 1492, when Isabella and Ferdinand, the Catholic monarchs of Spain, expelled Jews from the Kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, a few Sephardim came to settle in Trikala, then already part of the Ottoman Empire. Later joined by Jewish migrants from Sicily, Portugal, Verona, and Hungary, the community grew and, by the beginning of the 1900s, it counted close to 500 members in a city of about 25,000 people.

“It was a stable Jewish community—not big in numbers but viable,” said Kostas Mihalikis, a historian and the author of The Jewish Community of Trikala 1881-1940. “Jews were accepted in every sector of social life; [there were] no signs of discrimination.” By virtue of its geographic location, Trikala served as the middle point between the Romaniote community of Ioannina to the west and the largely Sephardic communities of Larissa and Volos to the east. “Trikala was the [crossroads] for these Jews,” Mihalikis told me. “They met here in Trikala.”

With three active synagogues—Romaniote, Sephardic, and Sicilian—a Jewish school, and a monthly magazine Israel started by Asher Moissis, a well-known Greek Jewish author and community leader, the Trikala Jewish community thrived before WWII. But, unlike their neighbors to the north in Thessaloniki, the city’s Jews were also integrated into the local Greek society. They sat on boards of various institutions, spoke Greek without an accent, and participated in the political life of the city. This, according to Mihalikis, was one of the reasons that Jewish casualties in Trikala and the surrounding areas during the Holocaust were among the lowest in Greece.

Initially occupied by Italy, the city’s Jewish citizens didn’t suffer the same kind of harassment as those who lived in territories under German control. With news of persecution and deportations arriving from German-occupied Thessaloniki almost daily, Trikala’s Jews had time to prepare. A few sought and found shelter with Greek families in the mountainous villages, others were hidden by partisans, and yet others escaped to Athens. When Germans entered Trikala after the Italians surrendered to the Allies in September 1943, more Jews left the city assisted by the National Liberation Front, the main Greek resistance movement during the occupation of Greece. “One of the reasons people in Thessaloniki couldn’t escape was because it was easy to understand who was a Jew,” said Mihalikis. “In Trikala [the Nazis] couldn’t understand that [easily].”

For the next several months the Nazis tried to lure the Jews back to Trikala. “[The Germans] told them, ‘You do not look like the Jews of Thessaloniki and, therefore, you have absolutely no danger,’” Victor Venouziou told me via email. A few came back driven mostly by hunger, cold, and difficult conditions they’d found in the mountains. “The inhabitants of mountain villages weren’t prepared to accommodate such a large number of people. They were poor with little food,” Venouziou said.

“At [the same] time many Jews believed the lies Germans told them.” On March 24, 1944, those Jews who returned and stayed were arrested and sent to Larissa from where, together with Jews of other surrounding towns, they were put on a transport to Auschwitz.

About 300 Jews came back to Trikala after the war but most didn’t stay. To rebuild their lives many decided to move to larger cities such as Athens and Thessaloniki or to leave for the United States and Israel. Today the Jewish community of Trikala numbers around 40 people. Only one synagogue—the Romaniote Kal Yavanim—survived the war. Currently under reconstruction, sponsored by the German government with contributions from other Jewish communities of Greece and the Greek Jewish diaspora, it’s a repository of memories of an active Jewish life in the city as well as a symbol of the community’s hopes for the future. “[We] might have only a few people nowadays,” Jacob Venouziou told me via email, “but [we] still keep the same interest in Jewish life.”

Both the municipality and the Jewish community of Trikala hope the new monument won’t suffer the same fate as other Holocaust memorials and Jewish cemeteries in Greece. The memorial in Thessaloniki has been vandalized several times since its unveiling in 1997—four times alone last year; a memorial in Kavala was sprayed with paint two weeks after its opening; and, only a month before Trikala’s memorial inauguration, the city’s Jewish cemetery was desecrated. With the rate of anti-Semitism the highest in Europe and vandalism against Jewish sites on the rise, Greece has recently joined forces with Israel to combat anti-Semitism, xenophobia, and racism.

“This recent attack [on Trikala’s Jewish cemetery] reminds us that perseverance of the historical memory and respect for diversity is a continuous fight against the selective oblivion, prejudice and violence against the ‘other,’” Jacob Venouziou said in his speech during the unveiling. There is hope that the new Holocaust memorial will contribute to this remembrance. Mihalikis, who teaches history in high school, also hopes it’ll stimulate learning. “I regularly take students on walks around the old Jewish quarter and one time our principal came with us,” he said. “She told me later that close to 30 bystanders gathered to hear me speak. People want to know this history.”

A few blocks south from where the Trikala Holocaust memorial now stands are the banks of the river Lithaios, whose name has roots in the ancient Greek verb λήθω [litho], meaning to forget. Yet forgetting is exactly what the town wants to avoid with this new memorial. “Close to Lithaios river, the river of oblivion,” Mayor Papastergiou said in a speech, “we keep our memories alive.”